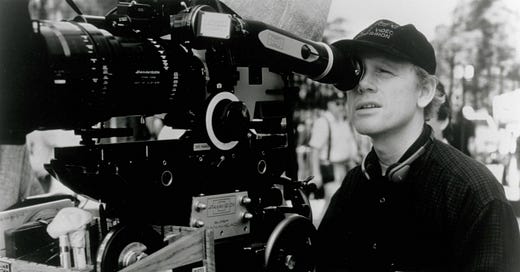

Ron Howard on the Art and Science of Testing Films

Lessons from Hollywood's Greatest Collaborator

"It's still art."

This simple declaration from Ron Howard captures the essence of what's made him one of Hollywood's most enduring and respected filmmakers. With over 30 films and five decades behind the camera, Howard has mastered the delicate balance between creative vision and audience response.

"The audience knows what they like and what they don't like," Howard explains on Kevin Goetz's podcast Don't Kill the Messenger. "They don't necessarily know why."

For filmmakers and storytelling enthusiasts, Howard's approach to audience testing offers a masterclass in balancing craft with commercial appeal.

Despite his Oscars, Emmys, and generations of box office success, Howard still gets nervous before test screenings. "I both dread it and depend upon it," he admits, "because I've learned that it makes the films better," Howard shares. This willingness to place his unfinished work before strangers, whose reactions might confirm his worst fears, has kept Howard's films relevant through decades of changing tastes.

Howard's journey with audience testing began early. After leaving his acting career on Happy Days to pursue directing, he felt immense pressure to prove himself.

"In those first couple of films, I was so mortified that my age was going to somehow hurt me," he remembers. "I felt like I had to have every answer, had to be strong and dig in and fight for everything."

The results? "My work was okay... but it wasn't as good as I wanted it to be."

His breakthrough came when he learned to invite other perspectives, including those of test audiences. "Slowly but surely, as I began to be a little more comfortable with collaboration, the quality of my work just jumped."

Reading the Room vs. Reading the Cards

Like many veteran filmmakers, Howard has developed a sense that goes beyond the numerical data on audience response cards.

"You can tell in a room with 250 people whether they are enjoying this or not," he observes. "You can also tell if there are certain slow parts, if there's levity, if there's comedy. It all comes through atmosphere."

Kevin Goetz, who has worked with Howard on more than half of his films, confirms this feeling: "You feel the air being sucked out of the room." This atmospheric reading complements but doesn't replace the hard data, giving directors both the "what" and the "why" of audience response.

The Commercial Arts: Finding Balance

Howard views filmmaking as "the commercial arts," borrowing producer Chris Meledandri's term. This isn't a concession but a recognition of reality—film is both artistic expression and commercial product.

"It begins with art," Howard insists. "It begins with a desire to communicate something... Every story has a set of principles, values, narrative values."

The audience feedback doesn't replace these values; it helps communicate them more effectively. "If you tell a joke at a party and you don't tell it very well, it doesn't get much of a laugh," Howard explains. "But you know there's something funny there. Maybe the next time you tell it better, and it does get a laugh. The spirit of the joke remains the same, but the delivery improved." This captures Howard's philosophy: test screenings help refine the delivery, not change the joke.

When to Hold Firm

Not all audience feedback should be acted upon. The key is understanding which criticisms address your film's core purpose and which don't.

"Sometimes you may say, 'No, I'm going to leave that disruption because it has other values that I don't want to let go of,'" he explains.

What matters is consciously making the choice, understanding what you prioritize and why. "Then it's at least an informed decision. And it's still art." This nuanced approach has helped Howard navigate both critical darlings like Apollo 13 and commercial blockbusters like The Da Vinci Code.

Howard cautions against blindly applying audience feedback: "You have to be careful that you don't start sanding things away so much that everything becomes bland." The director's job is to recognize and resolve conflicts, sometimes by removing problems and other times by finding solutions that preserve what works while addressing what doesn't.

Always Learning

After five decades at the highest level, Howard still approaches each project with a student's humility.

"This is the medium that can't be mastered," he says. "But if you don't think that's the good news, you should probably figure out another thing to do."

Howard has remained relevant through seismic changes in filmmaking precisely because he never stops learning from collaborators, audiences, and his own mistakes. This example offers inspiration and practical wisdom for filmmakers navigating an industry in constant flux: embrace collaboration, respect your audience, trust the process, and remember, through it all, it's still art.

The full conversation between Ron Howard and Kevin Goetz on "Don't Kill the Messenger" offers an even deeper dive into the filmmaker's philosophy and experiences with audience research. For filmmakers, film students, and anyone interested in the inner workings of Hollywood, it provides a valuable lesson in the delicate balance between creative vision and audience response, and how one director's commitment to that balance has created some of cinema's most beloved stories.